My mom, a retired Kindergarten teacher, looked at the packaging of a building toy. She pointed at the silver sticker on the box — emblazoned with the acronym “S.T.E.M.” — and laughed. “You know, in my day, we used to call this ‘building with blocks.’ Now everything is STEM. It’s the same thing, just a different name.”

She’s right, of course, about the buzzwords and trends of the education world. Toy companies, curriculum manufacturers, and academics are constantly rebranding the same basic principles of learning. But the emphasis on STEM education isn’t just a matter of rebranding blocks; nor is it simply a fad. The ubiquity of STEM in today’s schools reflects our shifting values as a society.

Our culture loves STEM because we love tech; and we love tech because it offers us seemingly endless prosperity and progress. (Not to mention tons of cute on-screen animations, flashing lights, and catchy sound effects.) The technology sector doesn’t just dominate our economy. Science and technology have become the main tool in our culture for problem-solving, decision-making, and values assessment. This technological mindset is reflected in our education system’s obsession with STEM. We believe we must “prepare our kids for the economy of the future,” and teach them to “think like scientists and engineers.” However worthy a goal, this is not enough, in and of itself.

Technology is a tool whose purpose we must define through an understanding of its social, environmental, and moral consequences.

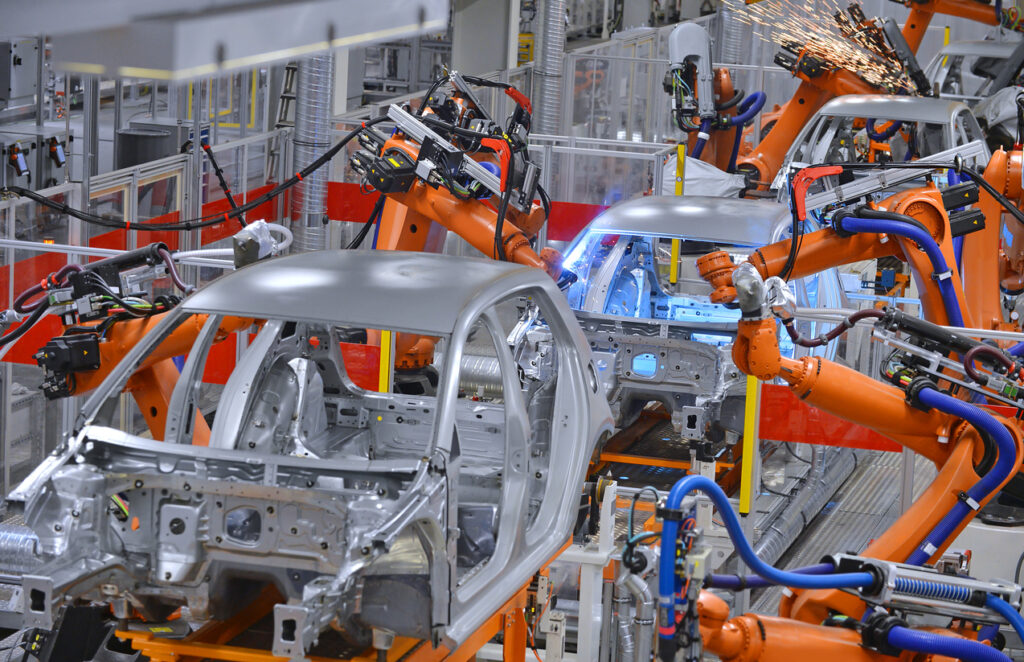

Yes, robots are amazing. The mechanics, the programming… the dancing on youTube. But there are negative social consequences to the wide-spread use of robots. The automotive worker who lost his job due to automation can attest to that reality.

To be technologically proficient, children should understand not only how to develop technology but how to direct it. Without this understanding — without balancing STEM with other modes of thought — the dominance of technology has dangerous implications for our environment and our social fabric.

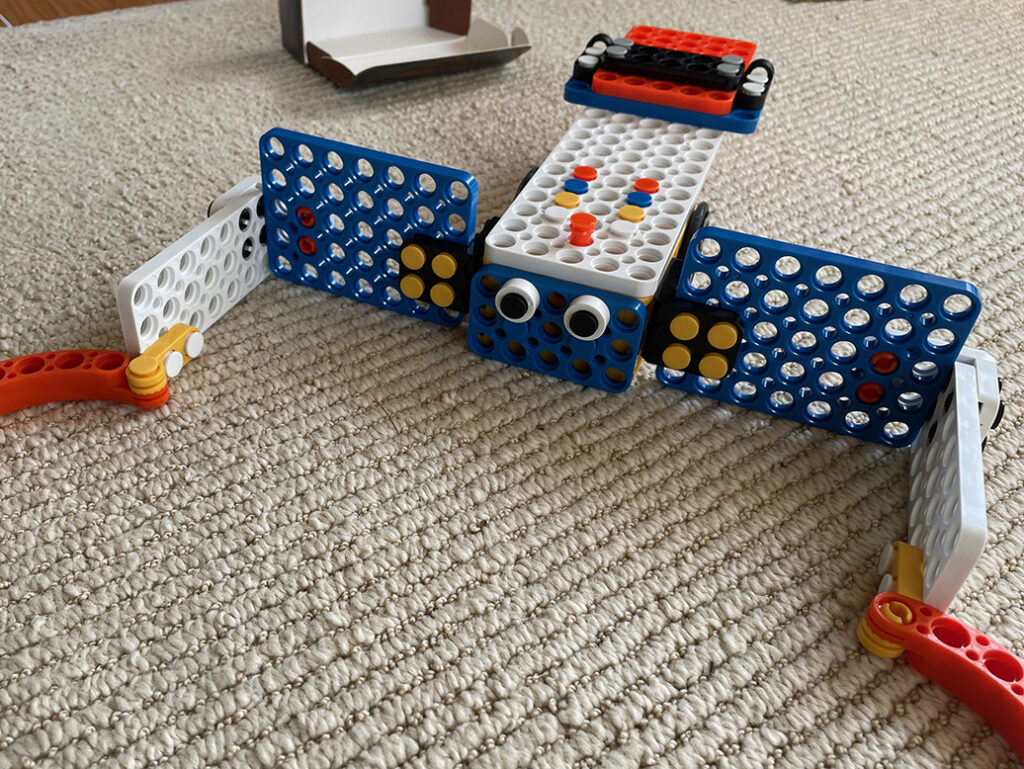

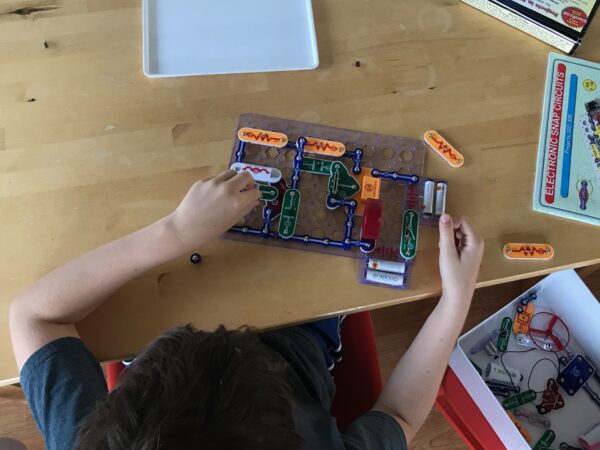

Now, don’t get me wrong. My family really does love STEM activities. We’ve been building propeller cars, catapults, and circuits since my son was old enough to hold a glue gun. As a natural tinkerer, my son is drawn to all things mechanical. In fact, developmentally, all children are more like engineers who experience the world through hands-on exploration and observation, than abstract-thinking scientists and philosophers.

So it makes sense for children to engage with math and science in an engineering and tech kind of way. And building is fun! Certainly, I know I would have enjoyed my own schooling more if we had been given greater opportunity to engage with craftsmanship, tinkering, and making.

It’s not STEM in and of itself that worries me. Rather, I’m concerned with just how much STEM has eclipsed other disciplines, and what that signifies. Florida, for example, recently passed legislation to alter their Bright Futures Scholarship program. The program, which used to guarantee free college tuition for its residents, based on merit, will now “tie the amount of aid students receive to the majors they choose in college… Students choosing favored areas of study would get more Bright Futures money.”1 Florida isn’t alone. There is a general trend by states toward “reducing funding [for] the humanities and providing added incentives for STEM majors at public institutions.”2

This emphasis on STEM is just another move toward purely economic-focused education, a system which designs learning objectives with the primary goal of generating profit and increasing GDP. It is a system that seeks, first and foremost, to churn out students who are marketable employees to the science and technology sector. (Ever wonder why Bill Gates is so involved in education?) Never mind students’ understanding of civics, democracy, and ethics. Will Google want to hire them? My computer science mentor put it bluntly when he said, “Only departments that make money for the school should be allowed to exist. Everything else is useless.”

But it’s dangerous to disregard the humanities because they aren’t “profitable.” When we put technology and engineering at the pinnacle of our educational system (and frame the more pure disciplines of science and math in terms of their service to tech), we position technology as a goal, in-and-of-itself. We forget that technology and engineering are really just tools– whose purpose and function we need to define. If we omit this perspective from our children’s education, we risk them losing agency to technology and technology corporations.

Technology is powerful. Any parent trying to limit their kids’ screen time can attest to the addictive nature of video games. The economics of software advertising incentivizes consumption. Users happily hand over our data and our privacy for the convenience of free apps. Social media platforms profit immensely from mining our private data and directing our attention to frivolous and sensational ideas at the expense of our mental health. We even apply gender norms to computers. We just aren’t very good at separating technology from ourselves. Without a broader education, we only further risk becoming tools of the technological elite.

The humanities are a record of this social wisdom. If we diminish the role of the humanities in education, we end up in a state that Vindana Shiva dubs ontological schizophrenia, where “the knowledge of how to make a product or develop a technology is separated from awareness of the impact of that product or technology on nature and society.”3

When we disregard the humanities, we end up with the absurd perversion of thought that leads to Facebook employees thinking they’re making the world a better place (despite having a negative impact on user mental health and democratic institutions), and people like Bill Gates thinking that they are saving the environment by corporatizing seed banks. We end up praising Elon Musk for offering a hundred million dollar prize for a solution to carbon capture, while disregarding the elegant environmental mechanism of carbon capture that evolved with our planet over hundreds of millions of years… trees! Such are the limitations of the technological paradigm. We quite literally lose sight of the forest for the trees, or in this case the ecological value of trees for our consumptive greed.

The extreme version of this viewpoint is the myth of the technological-fix, in which we believe that technological innovation can solve all of society’s problems. If we believe that technology has this capacity, then “the ethical, legal, economic, religious, or political aspects of a social problem can be ignored or bracketed. Once the technological problem is solved, the solution can be implemented and the entire problem thereby resolved, thus shortcutting the trouble of dealing with other complicating issues” such as ethics and morality4. But of course, we can’t really shortcut ethics or morality. We can’t ignore human behavior.

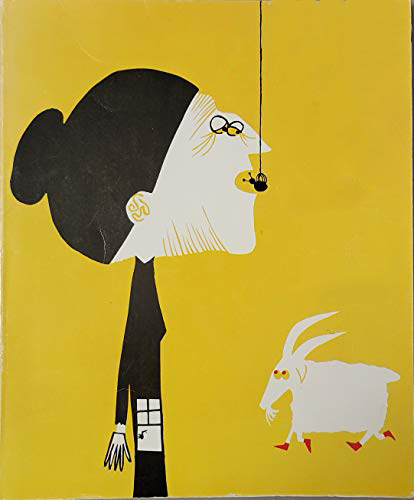

Consider the simple example of Jevons’ paradox, in which increased fuel efficiency actually leads to greater fuel consumption. Technology alone cannot solve the problems of human behavior. Trying to do so is a bit like the little old lady who swallowed a fly. The technological solutions that we swallow continue to become bigger and more impressive, but so do the new problems that these technologies generate.

My son used to take several classes at a STEM program in town. After class, he would talk excitedly about the technology news they discussed and the activities they did in class. One day he came home raving about lab-made meat, and its potential to reduce carbon emissions. He asked me if I would eat lab-made meat, and was baffled when I expressed hesitation and concern that maybe this lab-made meat wouldn’t end up being great for our health or our environment for some unforeseeable reason. I asked if maybe it would be better if people just ate less meat. He was shocked by my lack of faith in the products of a lab. My son, the boy who questions everything, was not applying his usual skepticism to science and technology. This is what happens when we become overly enamored with the achievements of tech.

It’s not enough for kids to practice critical and logical thinking within the scientific and engineering processes. They need to think critically about these fields themselves, and the direction of our efforts.

Wisdom demands a new orientation of science and technology towards the organic, the gentle, the non-violent, the elegant and beautiful… We must look for a revolution in technology to give us inventions and machines which reverse the destructive trends now threatening us all.5

To find these beautiful solutions, we need different kinds of thinkers. Yes, we need engineers and scientists. But we also need the omniscience of a novelist who can understand multiple perspectives and human striving. We need the wisdom and empathy of a Buddhist philosopher. We need the poet and biologist’s appreciation of nature along with the mathematician’s quest for perfect forms. We need to encourage our children to question their world (including technology), to strive for something better, and use technology with intention.

Schumacher said it best when he declared that: “Science will find a way out… only, I suggest, if there is a conscious and fundamental change in the direction of scientific effort.”5 STEM by itself is not enough.

SOURCES

- Odzer, Ari. (2021, March 16). Major Changes to Bright Futures Program Pass Florida Senate Committee. NBC Miami. https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/education-on-6/major-changes-to-bright-futures-program-pass-florida-senate-committee/2407148/

- Cohen, Patricia. (2016, Feb 21). A Rising Call to Promote STEM Education and Cut Liberal Arts Funding. NY Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/22/business/a-rising-call-to-promote-stem-education-and-cut-liberal-arts-funding.html

- Shiva, Vandana. (2020). Oneness Vs. The 1%. Chelsea Green Publishing. Page 23.

- Oelschlaeger, Max. (1979). The Myth of the Technological Fix. The Southwestern Journal of Philosophy, 10(1), 43-53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43155445

- Schumacher, E.F. (1973). Peace and Permanence. Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. Hartley & Marks. Page 20.

Good show