No matter how well thought-out our decision to homeschool, no matter how full of love and learning our days are, it’s kind of funny how worry creeps in. Sneaky little shadows of doubt can pop up at any minute. The truth is, homeschooling just feels risky in a way that schooling doesn’t, and there is no escaping the responsibility that it entails. So, no matter what I know logically, I can’t help but ask myself: Is my son learning enough?

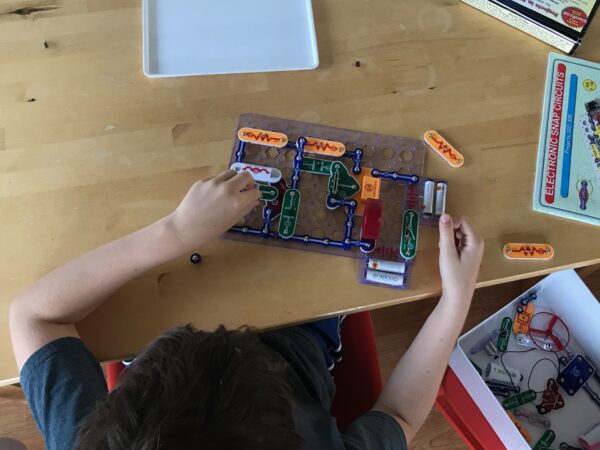

This worry hit me the other day when I realized that my son hadn’t done much science at all recently. In fact, I couldn’t remember the last experiment or building project he took up on his own. My analytical engineer was suddenly using every moment he had to read fantasy books — Wings of Fire, Warrior Cats, Dungeons & Dragons. So I had a flash of panic. Why wasn’t he interested in science anymore? Fortunately, I quickly realized how absurd I was being. After all, it wasn’t so long ago that I worried my son wasn’t interested in learning how to read!

From the absurdity of my doubt, I realized that I should applaud his progress and let him follow his new passions, rather than worry about his waning interest in other areas.

The fact is, curiosity isn’t linear. It ebbs and flows like any other organic process.

Take hunger, for example. When my son was a toddler, I remember thinking what a strange eater he was. Some days all he wanted to eat were fruits and vegetables. Other days, no amount of meat seemed to satiate his carnivorous appetite. Sometimes he barely snacked, while other times dinner went on for hours.

It turns out that this is actually quite normal. “The amount of food your kids eat and the types of food they gravitate toward at mealtimes will vary from one meal to the next. This is common and expected.1” Rather than worry, therefore, nutritionists stress the importance of honoring a child’s natural eating instincts.

The idea that we must eat the same ratio of foods at every single meal, that our bodies must operate based on external cues like time of day, what is served to us, etc, nutritionists now realize is actually de-regulating. That is, children have a natural internal system that lets them know when they are hungry and what their body needs. Through our own daily structures, prodding to “clean their plates,” and worry about them eating enough or too much, we can inadvertently socialize this out of them.

Similarly, it’s important that we honor our children’s innate curiosity. Children have a natural inclination to learn the things that are developmentally appropriate for them. If we trust their curiosity the way we trust their hunger cues, then they’ll learn to feed their creative selves and nourish their intellects.

The idea that kids must learn the same thing every day, in the same proportions — whether it’s seven, 45-minute, small servings or three big “blocks” of learning — can be as damaging to children’s natural learning cues, as the imposition of external food restrictions is to their hunger cues.

The lesson learned from any arbitrary doling out of curricular content is one that former educator and school critique John Gatto describes as “intellectual dependency.” Structured, compulsory curriculum teaches kids that they must “wait for a teacher to tell them what to do” and rely on others “to make the meanings of [their] lives…” Rather than let children guide their own education, choosing from the “the millions of things of value to study, [school boards] decide what few we have time for.2” When worry creeps in, it’s easy for homeschooling parents to adopt the same pattern as schools, doling out content to keep our children “caught up.”

In the same way that “positive food parenting is built on unconditional trust in your children’s ability to eat what they need to grow and flourish,1” positive learning requires we trust our children’s ability to feed their own curiosity. Interestingly, preschools and universities tend to embrace this model. They offer a plethora of learning choices – whether it’s building and art stations for toddlers, or a huge course catalog of opportunities for college students. They provide a giant menu for learners to choose from – based on their own interests, ambitions, and yes, sometimes whimsy.

Now of course, this doesn’t mean we let our kids binge watch Netflix all day any more than we would fill our cabinets entirely with M&Ms.

Just as we offer a variety of healthy options to our children at mealtime, we can surround them with a nourishing learning environment full of inspiring learning materials, take them to the library, connect them to others. We can set their table with healthy options. But we can’t force it. I don’t know anybody who learned to love a food they were forced to eat against their natural tastes. Rather than fight that pointless battle, why not help our children find something nourishing that they do love? After all, there are plenty of options.

When we chose to homeschool, we spared our children the constant comparison to peers that school kids face. By trusting our children, we can extend that grace to ourselves. We can give our children the freedom to pursue what they’re passionate about and give ourselves the joy of following their journey with greater confidence… or at the very least, a little less pressure and worry.

SOURCES

- Crystal Karges Nutrition, “My Child Will Only Eat Certain Foods At Meals What Should I Do?“

- Gatto, John Taylor. “The Seven Lesson School Teacher.” Dumbing Us Down, New Society Publishers, 1992, Page 7.