Imagine elementary school students in history class, making small tipis with wooden skewers and paper. They’re engaged and having fun. Now imagine that group of students outside in a field, learning traditional methods to lash and construct a tipi large enough for them to actually inhabit. They sit in the grass, practicing knot work. They work together to lash and raise the large posts. When they’re done, they hold a group meeting or tell stories in the space they just built. They have experienced community and teamwork, and may have come to understand culture and housing in a completely new way.

Similarly, consider the typical STEM activity of building model cars. Only, scale it up and take it outside. Instead of hand-held models, you have kids building old-school go karts, zooming downhill, and shrieking with excitement. If we can practice dreaming big and building big — even just occasionally — we can make learning that much more joyful.

But building big isn’t just about fun. When kids build with large-scale materials, they develop teamwork skills, since they have to work together to physically manipulate large objects; they get to use both fine and gross motor skills; and in the end, they have something truly inspiring, that more closely resembles the authentic experience or object that they’re studying.

I first learned the value of scaling-up accidentally, when teaching a 7th grade unit about ancient Rome. My co-teacher and I led a month-long project in which the students played the part of Roman engineers and planned a new aqueduct route across the empire. They spent weeks analyzing topographical maps, debating the pros and cons of different routes, and designing their plan. The culmination of the project was going to be a fun day of building model aqueducts with mini bricks.

Unfortunately, our plan for making the mini bricks was a total fail. It was the day of our culminating activity and we had no materials! Not wanting to disappoint the kids, I scrambled and found a local brickyard and loaded as much brick into the trunk and floors of my tiny Prius as I could fit.

During class, we set up shop in an unused portion of the school parking lot. After much initial moaning about the heat and the weight of the bricks, the kids started to experiment with building corbel arches (false arches) and started to get in the zone. The project took some serious manual labor, and consequently, some real team work. Because the bricks were so heavy, counter-levering them for the arch required multiple kids communicating and balancing pieces in harmony. To be successful, everybody had to participate.

In the end, each group’s brick wall was a couple feet tall, and strong and wide enough to support 6 middle schoolers standing atop the arches. The scale of the project gave it a feeling of authenticity, and the manual labor and teamwork involved gave everyone a sense of pride and ownership in the work. As they stood atop their arches, the kids were triumphant!

Years later, as a homeschooling parent, I watched this style of teamwork play out with my preschool aged son and his friends as they explored nature. The kids often had grand plans of building nature kitchens and forts out of large branches. Because the branches were so heavy, though, their plans were physically impossible without teamwork. If they wanted to succeed, they needed to communicate and move in unison to carry and arrange branches. From this genuine need came friendship, trust, and a strong sense of accomplishment. I watched kids who were just moving into the developmental stage of cooperative play master this kind of group work by grappling with large materials in nature.

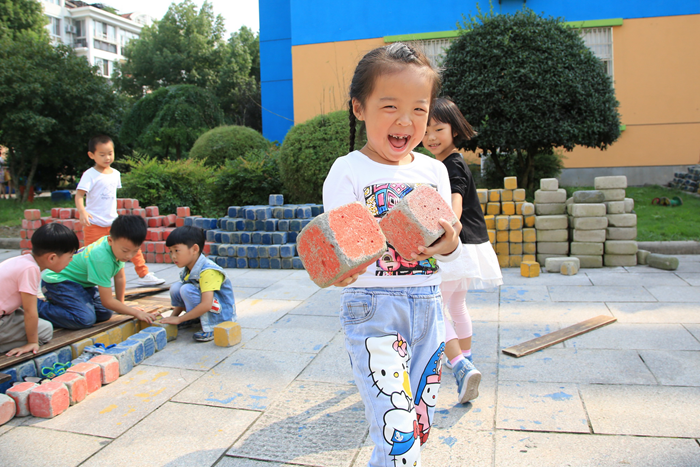

While nature schooling lends itself easily to scaled-up activities, our Roman aqueducts are a simple example of how it’s possible for public schools to engage in large-scale building, as well. Some schools — such as the Anji Play schools in rural China — have even managed to make large-scale, open-ended materials a foundation for their curriculum to “engage the child’s entire body and mind in the process of problem-solving” and to “invite children to engage in large-scale construction, design, combination, recombination, revision, imagination, and self-expression.” This whole body engagement is particularly important for younger children. Kids need to move — not just to burn energy, but to stay emotionally regulated. In contrast, smaller builds can often be frustrating for young children who are still developing fine motor skills.

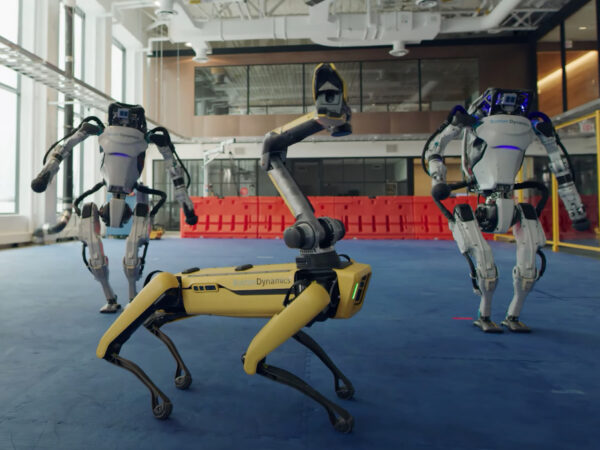

Teamwork, joy, and large-scale construction at Anji Play

Anji play is amazing, in part, because it is a public school system that has freed itself from the limits of school room thinking. This isn’t necessarily easy. Even as a homeschooler, free from many of the restrictions placed on school teachers, I often find myself thinking within the traditional classroom space of activities. It’s just the default way of thinking. Schools like Anji play are a reminder that it’s always possible to step outside of these limitations.

Whether in a school setting, in the forest or field, or even in our own backyards, if we remember to think beyond the physical restrictions of a classroom, we can scale-up some of our hands-on activities. We can help make our kids learning bigger, more collaborative, and more full of joy.