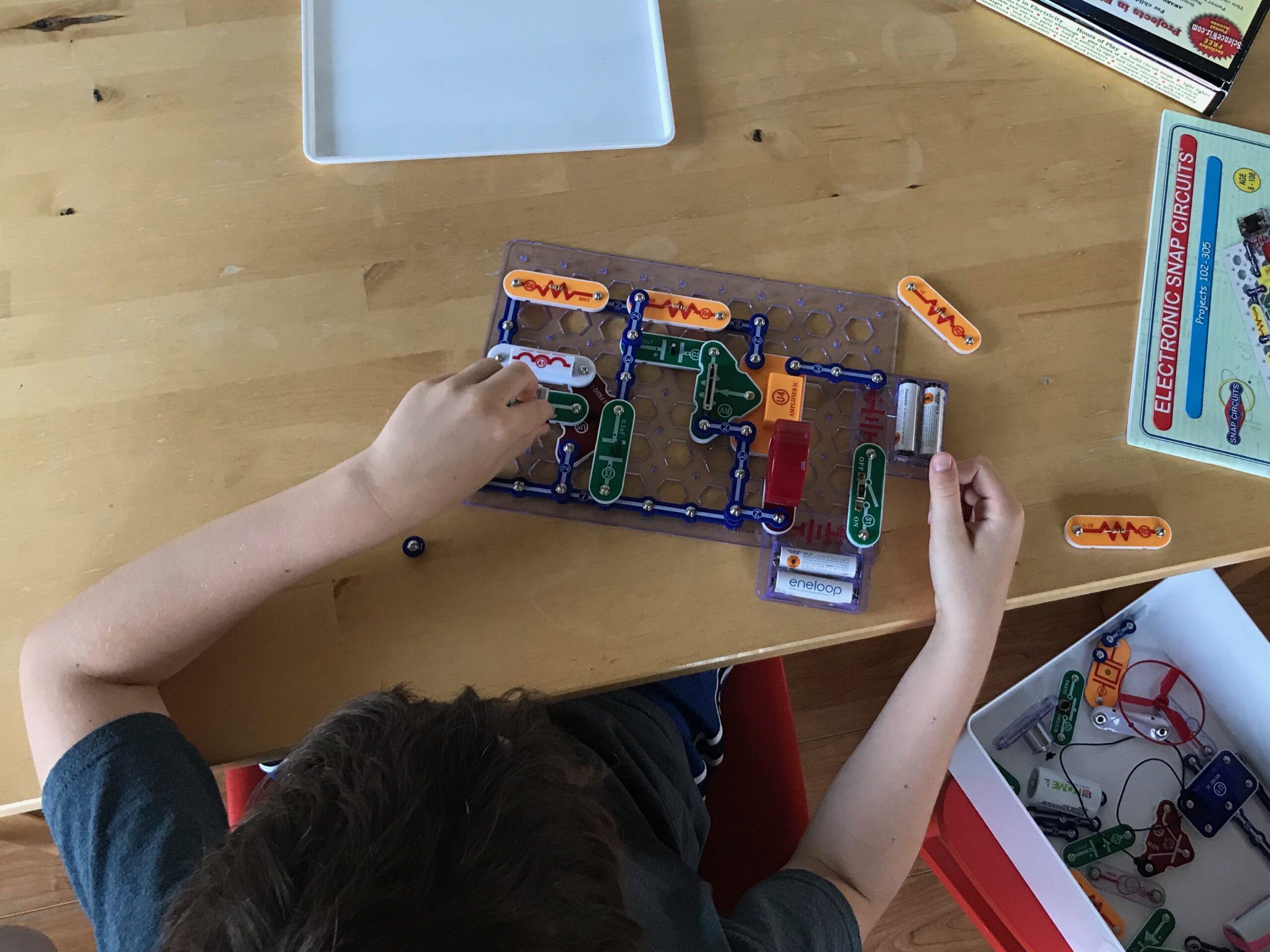

Lately, my son has been really into building with his Snap Circuits set. That’s him in the picture above, engrossed in his work. Notice the instruction book on the side? Yep. It’s closed. I tried my best, really, but I just couldn’t get him to open it.

I sat down next to him and flipped through the different circuit plans, oohing and aahing at the ones I thought he would find interesting. I asked questions about what the different components did. I even tried to organize the parts. Try as I might, he was not interested at all in following the directions. As he worked away– snapping pieces together, turning dials, and playing with motors– I realized that I was being way more annoying than inspiring. So, I gave up my crazy tactics, and let him experiment.

This can be hard to do. Even though I know enough to back off and let him do his thing, I often feel conflicted about it. Sometimes, I can’t shake the idea that my son would learn so much more if he just followed instructions. You know, do the jigsaw puzzle starting with the edges. Count loose objects going from top to bottom, or left to right, instead of in random crazy circles. Build the actual Rube Goldberg machine from the Rube Goldberg kit, instead of making marble-launching machine guns.

It can be hard to trust that children know how to learn– especially in cases in which their thinking is so incredibly different from our own. Fortunately, this week, the universe handed me a sanity check. To complement his snap circuits work, my son and I read Electrical Wizard, a biography of Nikola Tesla. The book opens with a quote from the inventor about his childhood play:

[A young inventor’s] first endeavors are purely instinctive, promptings of an imagination vivid and undisciplined. As we grow older, reason asserts itself and we become more and more systematic and designing. But those early impulses, though not immediately productive, are of the greatest moment and may shape our very destinies.

Nikola Tesla

This is such a powerful reminder not to project our adult minds onto children. Yes, following instructions can yield seemingly more productive outcomes, but productivity is the province of adulthood. Imposing too much structure on children at an early age comes at a cost– the freedom to exercise creativity without limits, to imagine beyond what has already been delineated, and the belief that anything is possible. These are the gifts of a child’s mind.

When children experiment they don’t necessarily have an end-game in sight. They don’t need preconceived objectives. They play around and make observations. They imagine, laugh, and try something new. Tesla reminds us, with the above statement, that these sparks of insight and joy may very well be the vision that discipline later serves.

It’s important, then, when we’re observing our children, to try to see things from their perspective. As a homeschooling parent, it’s easy to become so distracted by the closed instruction book that we fail to see the leg shaking with excitement, or the eyes darting around with joy. It’s easy for us to say, “Nope. That won’t work” when they propose something fanciful, so they don’t “waste their time.” We need to fight these impulses. After all, we might be wrong.

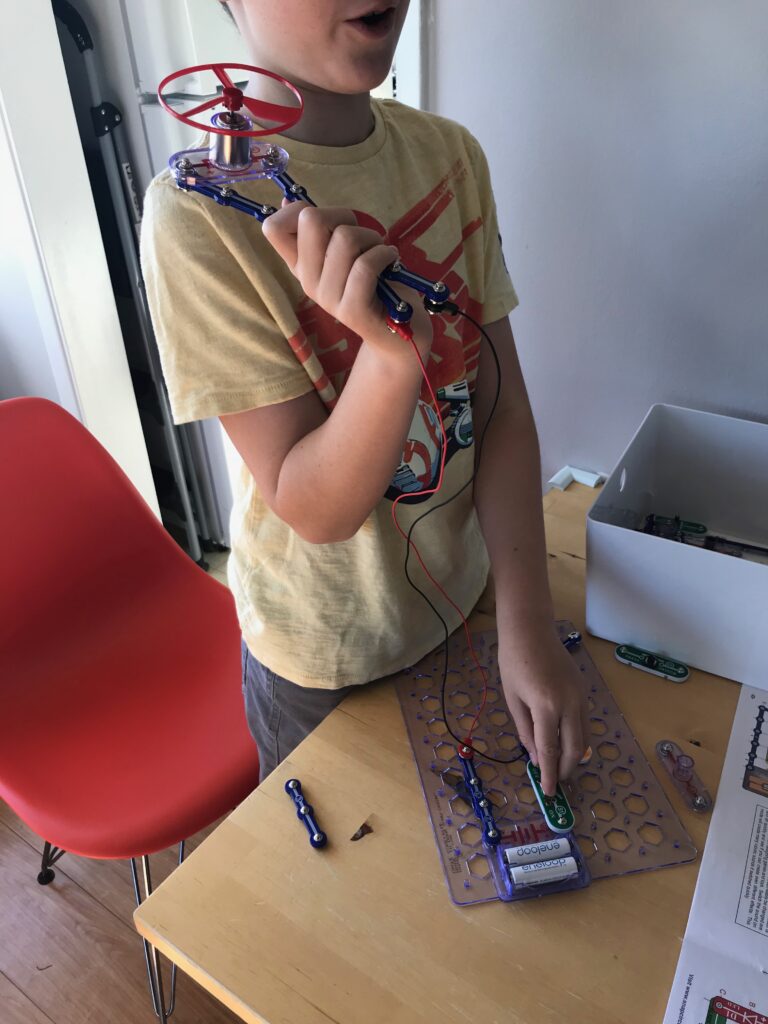

In the end, my son eventually flipped through the Snap Circuits book and checked out some of their suggestions. He did this, though, only after he tinkered and created his own invention off the grid — a fan launcher that provided tons of amusement and hilarity. He likely never would have invented this device if he had stuck to the manual. So I’m reminded that fighting my son’s own learning impulses — full of childhood joy and experimentation — in the name of “learning methods” would only have been counter-productive.

There will be time for discipline later, but maybe for now, at the age of 9, the learning objective should simply be: play around with this and see where it takes you. Quite likely the end destination will be more interesting and inspiring than the manual.