A little while ago, I was talking to a friend about my son’s newfound interest in astronomy. She became excited for him, and told me about some space-themed children’s songs. She even sang a couple of the catchy lines. Now, she wasn’t in any way offering the songs as a primary mode of studying astronomy. She just loves music and sees it as a bridge to connect to other concepts. Singing with kids is fun.

But the conversation got me thinking. I tried to imagine a bunch of NASA scientists, standing around a telescope, singing catchy tunes about their discoveries, like some strange barbershop quartet harmonizing about water on Mars. I just can’t picture it. Astronomers don’t need music to draw them into space. Space is infinitely complex and fascinating in and of itself. My son marvels at the idea of simultaneously expanding and shrinking black holes that spaghettify things, because black holes are a mind-blowingly powerful concept. Not because of a catchy jingle.

So why are these cutesy learning devices so prevalent? Why do we have kids sing songs to memorize the parts of a plant, instead of just letting them garden? Why do we read them stories about Lady Di of Amater building a round table, instead of letting them draw with a compass and look for patterns? Why not just help them see the beauty that is inherent in a subject at a level that is developmentally appropriate for the child?

It’s because it just wouldn’t work with our learning agenda. When schools and parents feel pressure to have every child cover so much material at such a young age, they face an engagement problem. Not all children are interested in the same things at the same time. And not all children are developmentally ready in Kindergarten to learn all the topics we want them to know. So schools end up needing to trick kids into engagement with multimedia displays, classroom games, and catchy tunes.

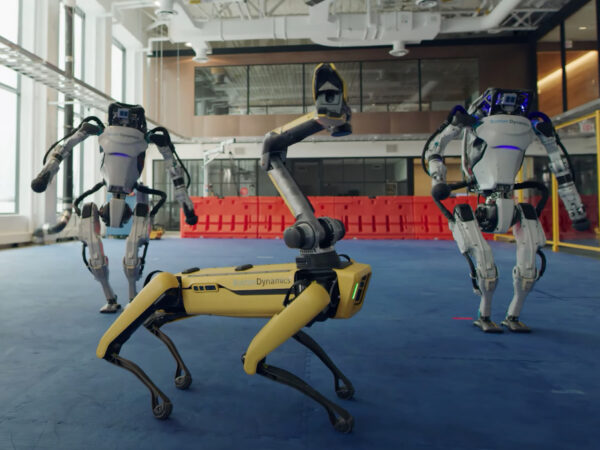

Children should be singing and dancing and playing. We know this. But we also, for some arbitrary and unknown reason, really want them to pick up a few good facts about our solar system along the way. So we contort astronomy to fit into the framework of children’s music. We take games, something we know they love, and try to use them as “teachable moments.”

OK. So, who cares! Kids are having fun, right? Isn’t that all that matters? The problem with this approach is two-fold. First, we’re not really connecting or engaging students with authentic learning within the field. It’s all a bit of a farce. And two, we’re implicitly telling kids that the material we’re trying to teach them, the intellectual and creative work itself, is dull. It’s a bit like sneaking vegetables into oatmeal or a cake. What are we saying about vegetables, when we can’t serve them directly? And what are we doing to that poor cake?

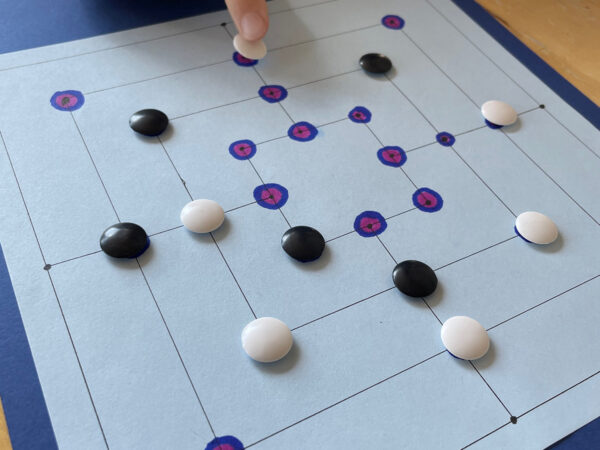

If it takes trickery to engage a child with a topic, then perhaps it’s the wrong topic, the wrong way to approach the topic, or simply the wrong time. Sing for the sake of singing. Paint for the sake of painting. Play games for the sake of fun and the thrill of strategizing, not because we have some secret ulterior learning plan. And when kids are interested, gaze at the stars in wonderment, gently lean over, and ask them: what’s out there? You’ll be amazed at what they come up with.